This magnificently bound album in two volumes dates to 1782-83. It contains detailed plans for some major engineering and architectural projects undertaken in France in the last years before the Revolution. The album is dedicated to the king, Louis XVI, by its author Jean Rodolphe Perronet, the chief royal engineer and architect, which explains the luxurious binding.

The content

The album includes both narrative and visual content. The latter consists of more than 60 copper prints, mainly plans and technical designs. It also contains views of some of the projected or actually built structures in the surrounding landscape or cityscape. It is those prints that are a real jewel of the albums, a marvel of art of draughtsmanship and engraving with an extremely fine texture and finish, defying our notions of the technical achievement of the pre-industrial age.

The narrative content of the album is mainly technical, containing detailed technical specifications and instructions for the engineering work, estimates of costs and various memoranda. It is clear that the text was not intended for the king to read. However, with his fascination for science and mechanics (it is known that Louis XVI had a passion for repairing clocks and was reportedly better at this than at ruling the country), I would not be surprised if the king took a secret delight in reading the technical stuff as well and that the author actually hoped he would.

What was actually built

There are just a handful of construction projects described in the album including mainly bridges and a canal. Not all of them were completed before the outbreak of the Revolution just a few years later (in 1789). Some of them never were, after the king to whom they were dedicated was executed and L’Ancient Régime was forever buried with him.

One of those that were completed is the new stone bridge at Neuilly-sur-Seine (Opening of Neuilly Bridge), now an opulent suburb of Paris. This bridge, which took ten years to build, stands directly on the straight axis radiating from Place Louis XV in front of Tuileries (now called Place de la Concorde as an apology for many people executed here during the Revolution) through the Champs Élysées (Plan de la route), intercepted now by the Arc de Triomphe at the very centre. This is probably the main street in Paris where all the most important public events and festivities have been taking place since the 18th century.

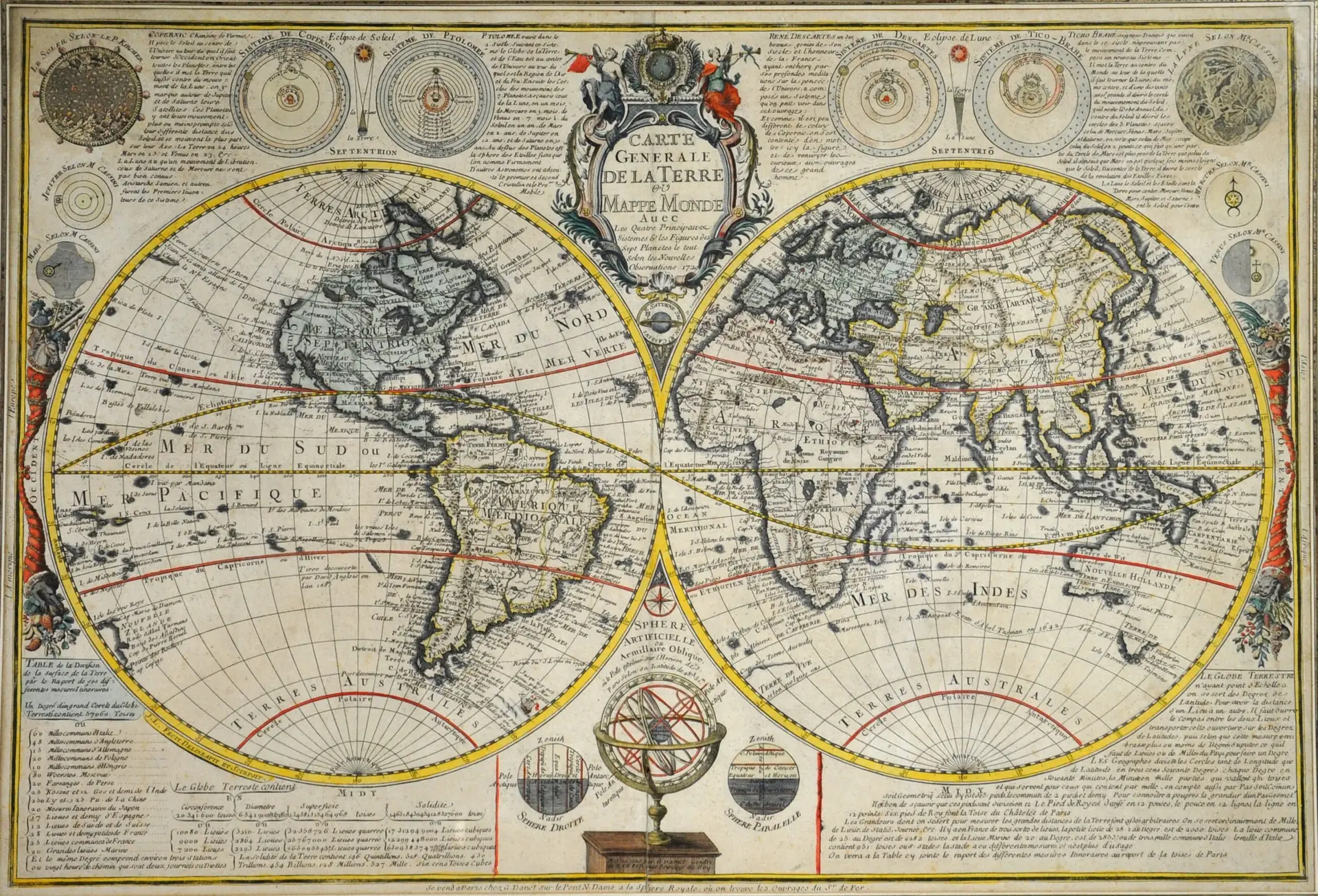

One of the projects that was not completed before the Revolution was a bridge across the same river Seine at the very edge of Place Louis XV linking it to the left bank of the Seine where Palais Bourbon stood (later replaced by a new eponymous Palace housing the National Assembly). There was a long stretch of the Seine west of the Louvre, as can be seen on this Map of Paris 1783 (as well as on the Plan Turgot), which no single bridge crossed. So building a bridge next to what was effectively the main square of Paris was quite logical, even inevitable. The first bridge was built during the Revolution and was called befittingly the Revolution Bridge (as can be seen on this Plan de Paris 1797), apparently based on Perronet’s design. The album includes a beautiful print with the view of what Perronet’s bridge must have looked like according to his initial design (View of projected bridge).

One can see the projected bridge on this plan included in the album, which shows its exact location with topographical accuracy. It extends across the Seine the straight axis originating from St. Magdalene church on the left and terminating in front of the Palais Bourbon on the right (see Perronet Plan Paris).

The beauty of technical designs

Some of the most amazing prints in the album are actually technical plans and drawings of tools and machinery. They are so absolutely perfect in their execution that they exude a kind of beauty you do not normally expect from technical designs. Look below at Tools and devices.

Quite a few prints in the album depict in great detail specific tools and machines that were used in the construction of specific objects. For example, this one (Machines Neilly) represents those employed in the building of the Neuilly bridge (see above). There are also a series of prints that detail various stages of the progress (Neuilly Bridge Progress 1772) of the construction of this bridge, year-by-year, revealing an almost obsessive concern with order and chronology.